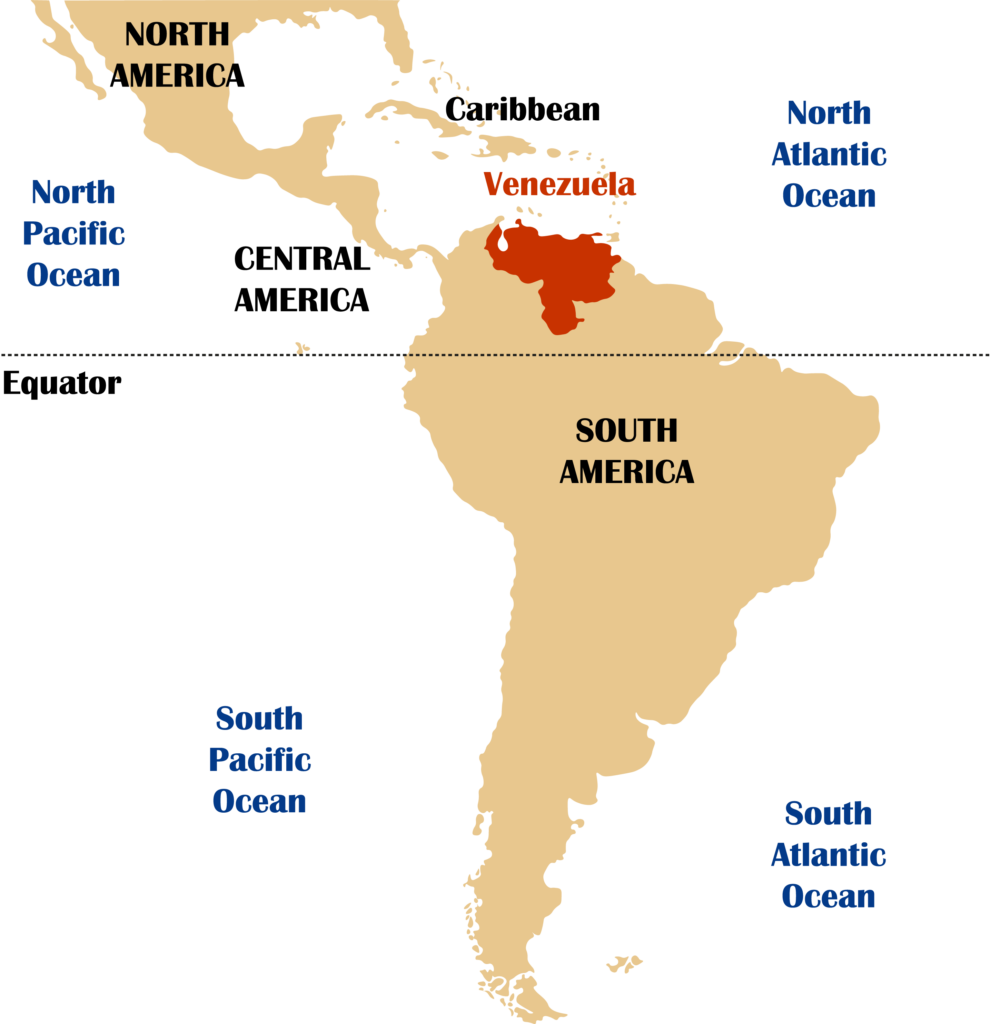

What's going on in Venezuela?

Before we talk about cacao in Venezuela, we want to give you a glimpse of what is currently going on in Ricardo’s native country. In the last 20 years, Venezuela is going through a deep political, social and economic crisis. A scenario that exposes the very foundations of the Chavista model.

The crisis in Venezuela began during the government of Hugo Chávez, during the period that corresponds to the so-called Bolivarian Revolution, and has continued with his successor Nicolás Maduro. It’s marked by

- STRONG HYPERINFLATION,

- INCREASED POVERTY,

- REAPPEARANCE OF ERADICATED DISEASES,

- INCREASE OF CRIME,

- INCREASE OF MORTAILITY,

- RESULTING IN MASSIVE EMIGRATION FROM THE COUNTRY.

The situation is by far the worst economic crisis in the history of Venezuela, and the worst worldwide since the mid-20th century (for a country that is not experiencing a war), worse than the 1985-1994 economic crisis in Brazil or the hyperinflationary crisis in Zimbabwe of 2008-2009. According to the UN, more than 7.2 million Venezuelans have fled the country (28/03/2023).

THE CACAO SECTOR WAS NOT IMMUNE TO THIS CRISIS. The same way it happened before in Venezuelan history (we elaborate on this below), the cacao sector was hit hard. Venezuela was the world’s leading producer of cacao until the end of the 18th century and traded under the rule of the Spanish colony. Today, it produces between 16,000 and 17,000 tons/year of cacao, representing only 0.04% of the total world production of this crop.

Is there a light at the end of the tunnel for Venezuela, at least when it comes to cacao and chocolate?

CACAO IN VENEZUELA

Before the 1600s

Researchers Humberto Reyes and Liliana Capriles de Reyes claim in their book ‘Cacao in Venezuela’ (2000), that the ‘Criollo’ cacao first spread in the ‘Sur del Lago’ sub-region formed by part of the states Zulia and Mérida. When the Spanish arrived in Venezuela at the end of the 15th century, cacao was widespread in several regions in the centre, south and east of the ‘Lago de Maracaibo’ basin.

Like the Aztecs, the Venezuelan indigenous would prepare a drink with cacao beans that they called CHACOTE, and offer their gods cacao butter by burning it in clay grills. They would also use the cacao bean as currency and for cosmetic and religious purposes.

The origin of cacao in Venezuela is linked to indigenous culture, exactly as it happened in Mexico or Ecuador, being influenced by Europeans after their arrival to the country. The Europeans discovered the potential of the precious seed, introducing it in their farms and plantations to then export and trade it.

1600s

According to the Venezuela Chamber of Cacao (CAPEC), the first data on cacao plantations in Venezuela – settled by the Spanish – dates back to the late 1600s, when it was first listed as a product produced in the state of Merida and exported to Spain.

1700s

The cultivation of cacao spread to the shores of the states of Aragua, Sucre and the Barlovento region. During this period, the export volumes ranged from 600 to about 2,230 tons/year. Between 1797 and 1800, cacao represented up to 66% of the total value of exports in Venezuela.

1800s

In the mid-1800s, the cacao production in Venezuela stagnated with an average of 5,000 tons/year (according to CAPEC), due to several events.

The War of Independence (1810-1823) and the successive civil unrest affected the cacao farms in the country. There was a shortage of workforce and also trade was interrupted.

In addition, the Trinitario and Forastero cacao varieties were introduced to Venezuela from the island of Trinidad. The hybridisation process that began from this moment meant that Venezuela no longer exclusively produced the prestigious Criollo cacao.

In the mid-1800s, coffee replaced cacao as the main crop of Venezuela’s economy and as the largest income generator. By the end of the century, the number of coffee farms had increased exponentially, demonstrating the decline of cacao cultivation in Venezuela.

1900s

Between 1900 and 1920, cacao volumes again reached a maximum high of 22,000 tons/year. At that time, the abundant oil resources in Venezuela were not exploited yet. Products such as cacao, coffee and sugar cane attained interesting export figures and were praised as the best valued agricultural treasures in the country.

The appearance of oil at the end of the 1920s, drastically affected the social and economic-productive structure of the country. Besides the rise of the oil economy, the increase of African participation in the cacao sector and some natural disasters (such as the cyclone in 1933 that destroyed the plantations in the Sucre state) also had a major impact on Venezuela’s cacao production and exports. After 1929, the cacao sector suffered from a prolonged and deep depression. The low international prices were not enough to cover the production costs and caused the deterioration and neglect of the plantations during the rest of the 20th century.

2000s and present day

VENEZUELAN CACAO EXPORTS REPRESENT ONLY A SMALL FRACTION OF THE WORLD PRODUCTION. HOWEVER, BEAN-TO-BAR CHOCOLATE MAKERS APPRECIATE THE VALUE OF VENEZUELAN CACAO, MOSTLY DUE TO ITS INTENSE FLAVOUR AND AROMA.

The crisis in the country has led the farmers to work under very limited and poor conditions, resulting in low quality cacao. The currency exchange restrictions and hyperinflation does not allow farmers to buy the products they need for their crops and, fearing that they will be robbed, they have no other option than to rush the fermentation and drying processes of the fruit, sacrificing its flavour. Delays in the delivery of export permits have paralysed many shipments. All this together results in buyers changing suppliers to take less risk.

The thieves who rob and kidnap cacao farmers are not only armed gangs but also officers belonging to the army. It is a common practice that trucks full of cacao are stopped by the army at the checkpoints. Drivers are sometimes forced to unload the merchandise at government warehouses. Many cases like this have been reported to the local authorities and newspapers but nothing has been done to make it better.

Despite the horrible crisis and plummeting economy, the cacao sector has been experiencing a boom in the last 5 years (THANKS TO BEAN-TO-BAR CHOCOLATE). The people (farmers and chocolate makers) still living in the country have found in chocolate a reason to stay and a way to earn a living.

The social entrepreneur María Fernanda di Giacobbe is the best example. She has spent years dedicated to teaching how to achieve it. She has travelled Venezuela explaining to the families how those plants they had forgotten in their gardens could become a source of livelihood. Sponsoring projects such as Cacao de Origen or Kakao Bombones Venezolanos, she has ‘fostered the wisdom of the communities’.

Returning to cultivating cacao could improve the crisis because it grows everywhere throughout the country and because there is not a Venezuelan who does not feel identified with it.